Video Sources 33 Views Report Error

Synopsis

In 1950, the young and fiercely talented writer Flannery O’Connor returns to her family home in Georgia after receiving a life-altering diagnosis: lupus, the same debilitating disease that claimed her father’s life. At just twenty-four years old, Flannery is thrust into a battle with an illness that not only threatens her physical well-being but also her dreams of literary greatness. As she grapples with the reality of her condition, Flannery’s imagination is ignited, leading her to confront profound questions about faith, suffering, and the nature of art.

Flannery’s mother, Regina, is a devout Catholic who has always struggled to understand her daughter’s dark and often scandalous stories. Regina’s deep concern for Flannery’s health is coupled with her desire to see her daughter embrace a more traditional, pious life. Yet, Flannery’s writing, characterized by its grotesque and sometimes shocking content, is her means of exploring the complexities of the human condition and her own turbulent relationship with faith. Her illness only intensifies these explorations, as she begins to see her suffering as both a curse and a potential source of creative inspiration.

Confined to her mother’s rural farm, Flannery’s world shrinks, but her inner life expands in extraordinary ways. She starts to question whether her art, which often delves into the macabre and the morally ambiguous, can still serve a higher purpose. Is it possible, she wonders, for scandalous art to glorify God? This question becomes a central obsession for Flannery, as she continues to write stories that challenge conventional religious sensibilities while grappling with her own beliefs.

As her illness progresses, Flannery also reflects on the role of suffering in the pursuit of greatness. She is haunted by the idea that true artistic achievement may require personal sacrifice, perhaps even to the point of self-destruction. Her father’s death from lupus looms large in her mind, a constant reminder of the fragility of life and the possibility that her own time is limited. This awareness fuels her determination to leave a lasting literary legacy, even as her body weakens.

Amidst her physical and spiritual struggles, Flannery’s writing flourishes. The isolation imposed by her illness allows her to focus intensely on her craft, producing some of the most powerful and provocative works of her career. Her stories, filled with flawed characters and unexpected moments of grace, reflect her deepening understanding of the complexities of faith and the human experience. In this way, her illness, though devastating, becomes a kind of blessing—an impetus for creative exploration that might not have been possible otherwise.

Flannery’s relationship with her mother also evolves as they navigate the challenges of her illness together. While Regina continues to wish for a more conventional path for her daughter, she gradually comes to appreciate Flannery’s unique gifts and the importance of her work. The bond between mother and daughter, though tested by illness and differing worldviews, ultimately strengthens as they find common ground in their shared faith and love for each other.

In the end, Flannery O’Connor’s battle with lupus becomes more than just a personal struggle—it is the crucible through which she refines her art and solidifies her place as one of the most significant writers of her time. Through her suffering, she achieves a profound understanding of the human condition, creating works that continue to challenge, inspire, and provoke readers long after her death.

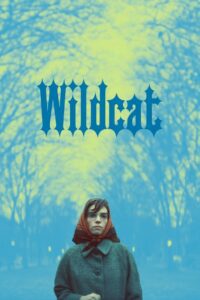

Original title Wildcat

IMDb Rating 5.8 928 votes

TMDb Rating 5.313 8 votes

Director

Director

Cast

Flannery O'Connor

Regina O'Connor

Robert "Cal" Lowell

O.E. Parker

Buzz Cut

Tom T. Shiftlet

Manley Pointer

Thomas

Elizabeth Hardwick

Jean